07-05-2024

The inaccuracies of real estate appraisers, whether accidental or purposeful, harm both financial institutions and those seeking to buy properties and can even trickle down to taxpayers. As a result, a study co-authored by a Purdue University professor suggests that a national database of property transactions and reported attributes should be created.

Mike Eriksen, professor of economics and director of the Dean V. White Real Estate Finance Program at Purdue's School of Business, teamed with two co-authors on “Attribute Misreporting and Appraisal Bias,” published in the Review of Finance. The researchers studied whether appraisers consistently reported objective property features, such as square footage, bedrooms and bathrooms, and lot size, to justify valuations associated with loan applications.

They found the assessments were often inconsistent, but for different reasons.

“Sometimes different appraisers can disagree in both subjective and objective assessments of a property, but it can be due to alternative access to the property or different approaches to measurement,” Eriksen says. “But in some cases, there is evidence of the same appraiser reporting different attributes for the same property. It’s a purposeful action to manipulate valuations to counter evidence that the purchase price would otherwise not have been justified.”

Eriksen and his fellow researchers, Chun Kuang, associate professor at the University of International Business and Economics, and Wenyu Zhu, associate professor at Renmin University of China, partnered with a large financial institution to create a database of reported property attributes associated with 4.6 million loan applications from 2013-2017. The database of attributes included both the property associated with the loan application and the reported attributes of nearby recent property transactions selected by the appraiser to assign the value.

The study found that most of the manipulated differences were likely to occur in the reported living area. Eriksen says that while most of the manipulations were upward and may seem like a victimless crime, there were consequences to the actions.

“Although foreclosures were relatively rare during the sample period, the borrowers of properties with manipulated values were eventually 9.8 percent more likely to become seriously delinquent in their subsequent loan payments,” he says. “There is harm done to financial institutions due to increased delinquency, but there is also a cost to other borrowers, who will pay slightly higher interest rates on their mortgage loans as a result.”

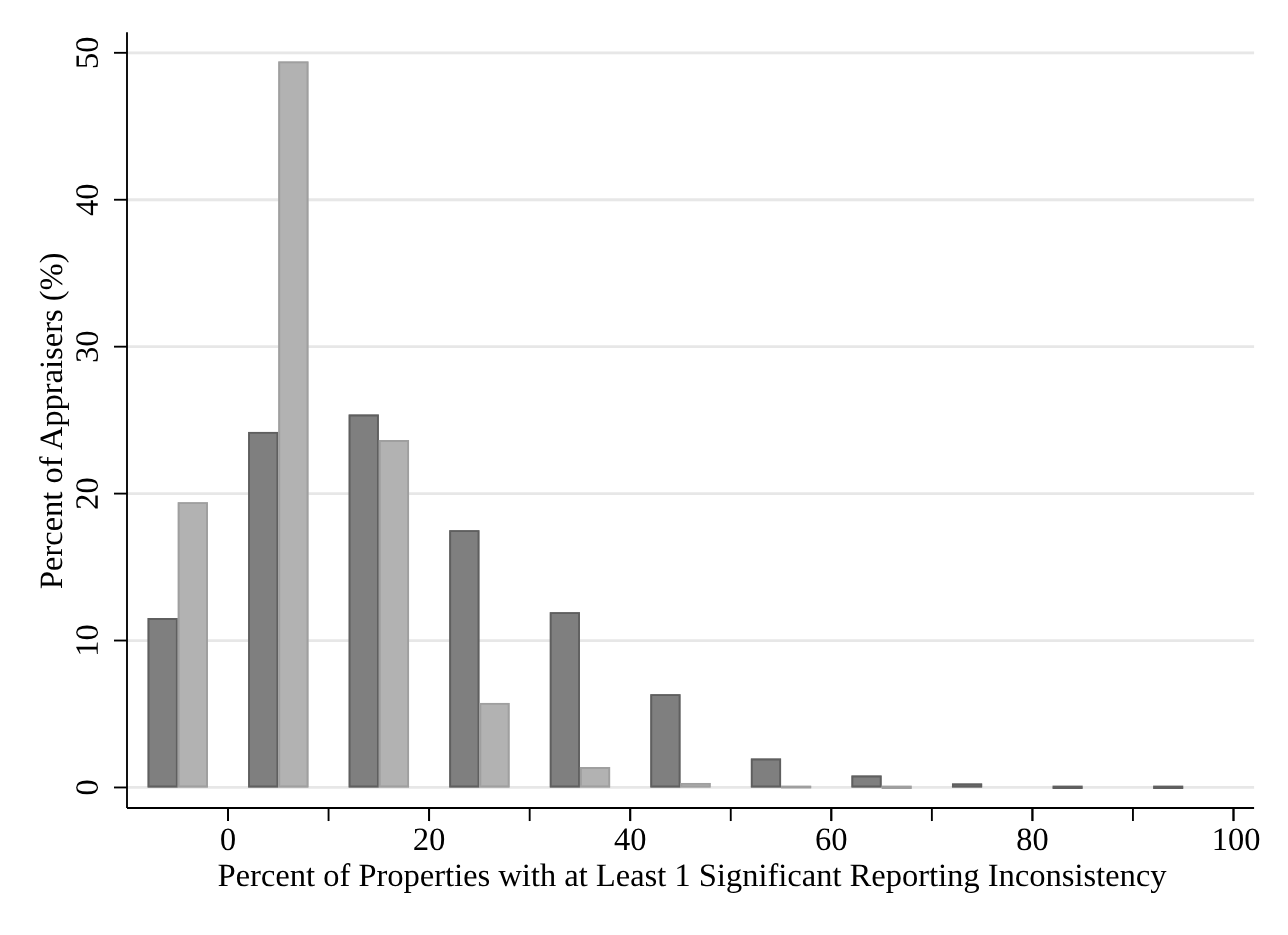

The study found that about two-thirds of appraisers have at least one significant reporting anomaly associated with 10 percent of their appraisals.

Eriksen says the financial crisis of 2008 was spurred by the overvaluation of residential properties, although the evidence is unclear whether it was driven by appraisers’ naivety or fraudulent actions. In addition, with an ever-increasing reliance on data to help make decisions, the underlying sources of that information should be scrutinized.

One solution is a national database of property transactions. Providing appraisers access and holding them accountable to use consistent attributes of comparable transactions could lower potential bias and enhance the liquidity of mortgage loans supported by those valuations.

Eriksen says the risks of not providing such access go beyond borrower and lender.

“Failure to price properties correctly could lead to lower capital reserves and greater exposure of taxpayers to future crises. If valuations are more accurate, it could prevent some inexperienced borrowers from paying a purchase price above market value, which will save the economic costs of foreclosure upon themselves and surrounding property owners,” he says.