02-12-2026

How does the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy affect inflation, employment and economic growth? This occurs by the transmission of monetary policy through the financial markets to the real economy. This point was made by Federal Reserve Bank of New York President William Dudley in a 2017 speech. He notes: “In sum, financial conditions affect households’ and firms’ saving and investment plans and, therefore, play a key role in influencing economic activity and the economic outlook.”

While financial conditions cover a broad range of factors, Dudley explains that “… financial conditions can be broadly summarized by five key measures: short- and long-term Treasury rates, credit spreads, the foreign exchange value of the dollar and equity prices.”

The Chicago Fed produces a Financial Conditions Index. Values above zero indicate tightness in financial conditions, while values below zero indicate looseness in financial conditions. Their series starts in 1970.

Tight financial conditions can occur during periods of stressed financial markets, such as the OPEC oil price shock in the mid-1970s and the Financial Crisis. Tight financial conditions can also occur when the Fed has to impose restrictive monetary policy to bring down inflation, as occurred during the Volker Fed in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Looking more recently, financial conditions were loose following the COVID health pandemic. Financial conditions began to tighten in 2022 with the Fed’s aggressive increases in its policy rate. However, financial conditions peaked just shy of neutral in November of 2022 prior to the end of the Fed’s tightening cycle. Financial conditions have subsequently eased, returning to where they were at the end of 2021.

As President Dudley makes clear, financial conditions and monetary policy do not move in lockstep; rather, they each influence the other. However, we can use financial conditions to provide another way to estimate the neutral real short-term interest rate — r-star. Reminder: r-star is the theoretical short-term real interest rate that allows the economy to operate at full employment with stable inflation.

We can define “monetary conditions” at a point in time to be the difference between the effective Federal Funds Rate (FFR) also known as the target interest rate set by the FOMC, and the neutral nominal policy rate — that is, the value of r-star plus 2 percent. We can then ask what values of r-star over time produce monetary conditions that “best fit” the history of financial conditions. In doing this exercise, we can impose that r-star changes smoothly over time with no jumps or sharp reversals.

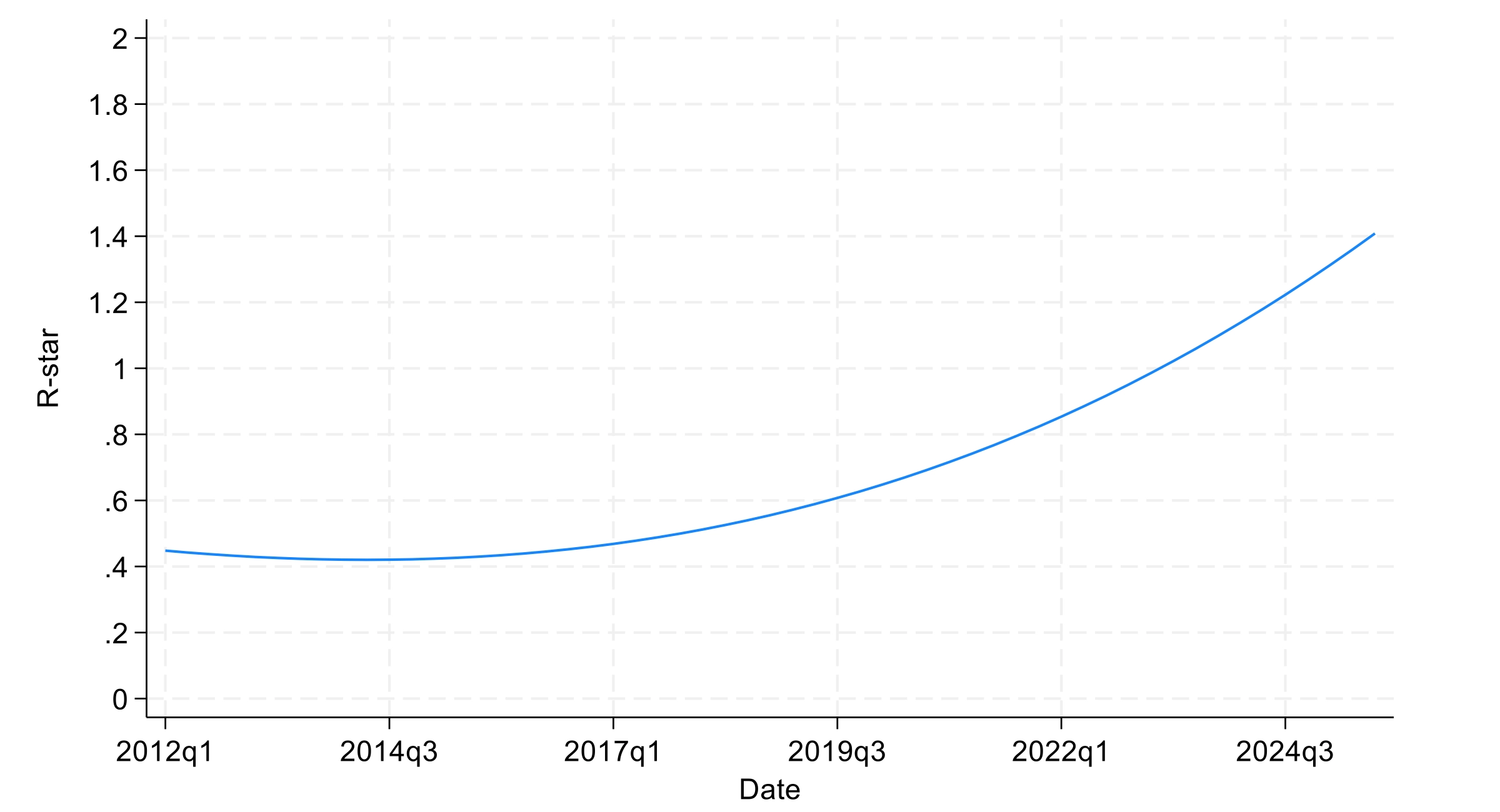

Doing this exercise generates the following estimates of r-star starting in 2012.

These estimates conform to the pattern in estimates of r-star from macro models that we discussed in my January Daniels Insights post. The best fit estimate indicates a current value of r-star of 1.4 percent.

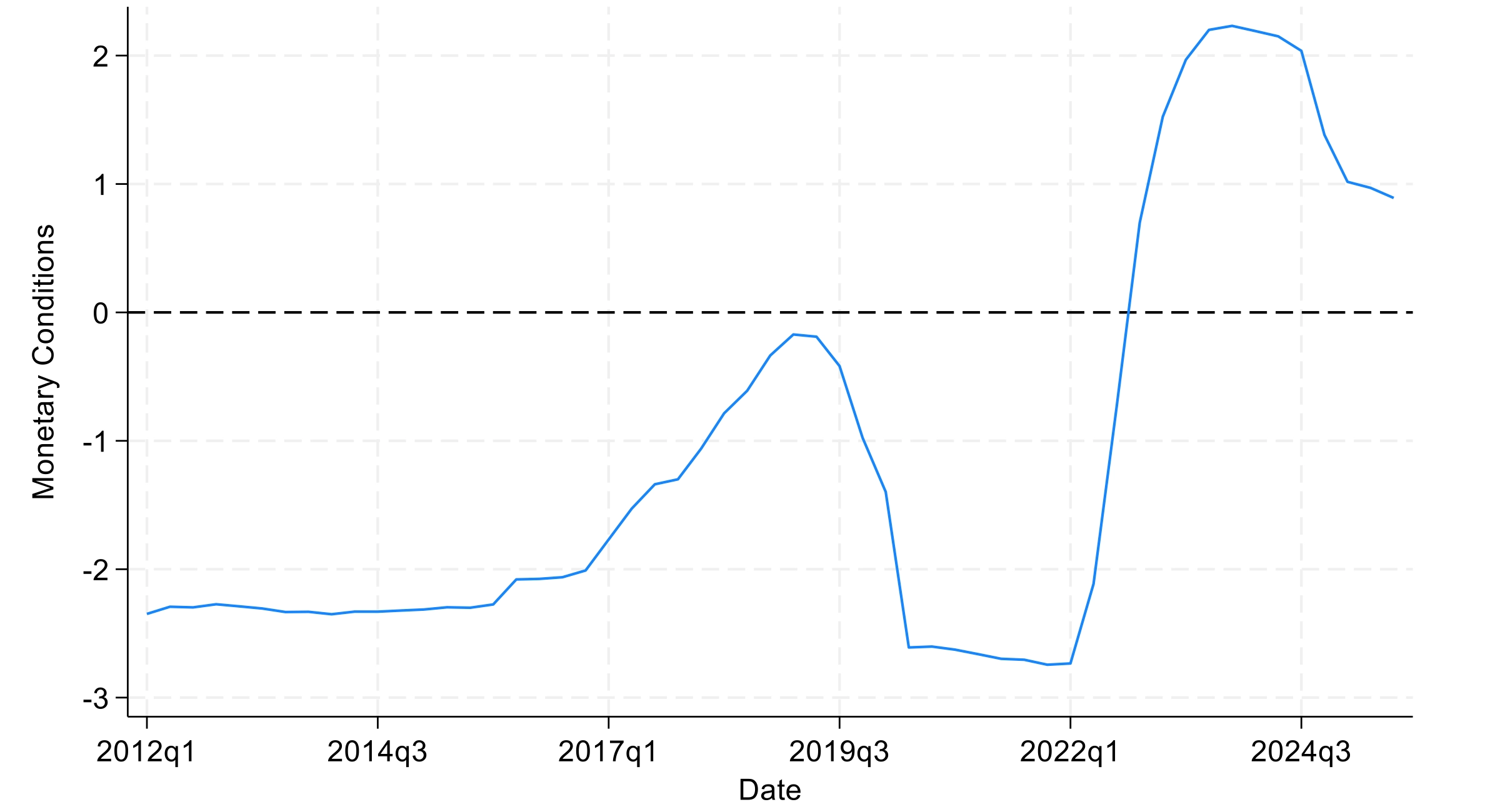

We can use this estimate of r-star to generate the “neutral” monetary policy rate since 2012. We can then create a monetary conditions index, which is the effective funds rate less the neutral policy rate. Positive values would indicate restrictive monetary conditions, while negative values would indicate accommodative conditions.

Post financial crisis, the Fed maintained accommodative monetary conditions for several years. As the economy gained momentum during the first Trump administration, monetary conditions moved toward neutral. In response to the COVID health pandemic, the Fed aggressively relaxed monetary conditions. The Fed then sharply reversed course in 2022 in response to the rapid increase in inflation. Prior to the last three rate cuts, monetary conditions indicated around a percentage point of tightening.

The Fed’s three 25-basis point cuts toward the end of 2025 reduced monetary conditions to close to zero. This is inconsistent with the characterization by Chair Powell in his December 10 press conference that monetary policy is “… within a range of plausible estimates of neutral …”. The question is whether this is the appropriate financial and monetary condition given that the latest Dallas Fed Trimmed Mean Inflation rate was 2.8 percent in November. If the Fed were focused on returning inflation to target, a Taylor rule would indicate that its monetary policy was better calibrated prior to the 75-basis point reduction in its policy rate.

The Fed has been missing its inflation target now for five years. Recently, the FOMC decided to focus on the employment side of its dual mandate. The implied value of r-star from financial conditions matches some model-based estimates that suggest that r-star has risen from around 0.5 percent in the early 2000s to between 1 and 2 percent. Both financial conditions and monetary conditions indicate that the Fed is no longer actively trying to reduce inflation. A majority of the FOMC appears to believe that inflation will come back down to target on its own. In considering this strategy, we should keep in mind the insight from Jessie Jones:

“I’m sorry, but nothing ‘just happens.’ Stuff happens because either we make it happen or we let it.”

The Fed is ready to let inflation come down to 2 percent. It would be much better if they worked to make it come down to 2 percent.

Joseph Tracy is a Distinguished Fellow at Purdue University’s Daniels School of Business and a nonresident senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. Previously he was executive vice president and senior advisor to the president at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. He regularly contributes insightful posts about financial markets to Daniels Insights.