09-02-2025

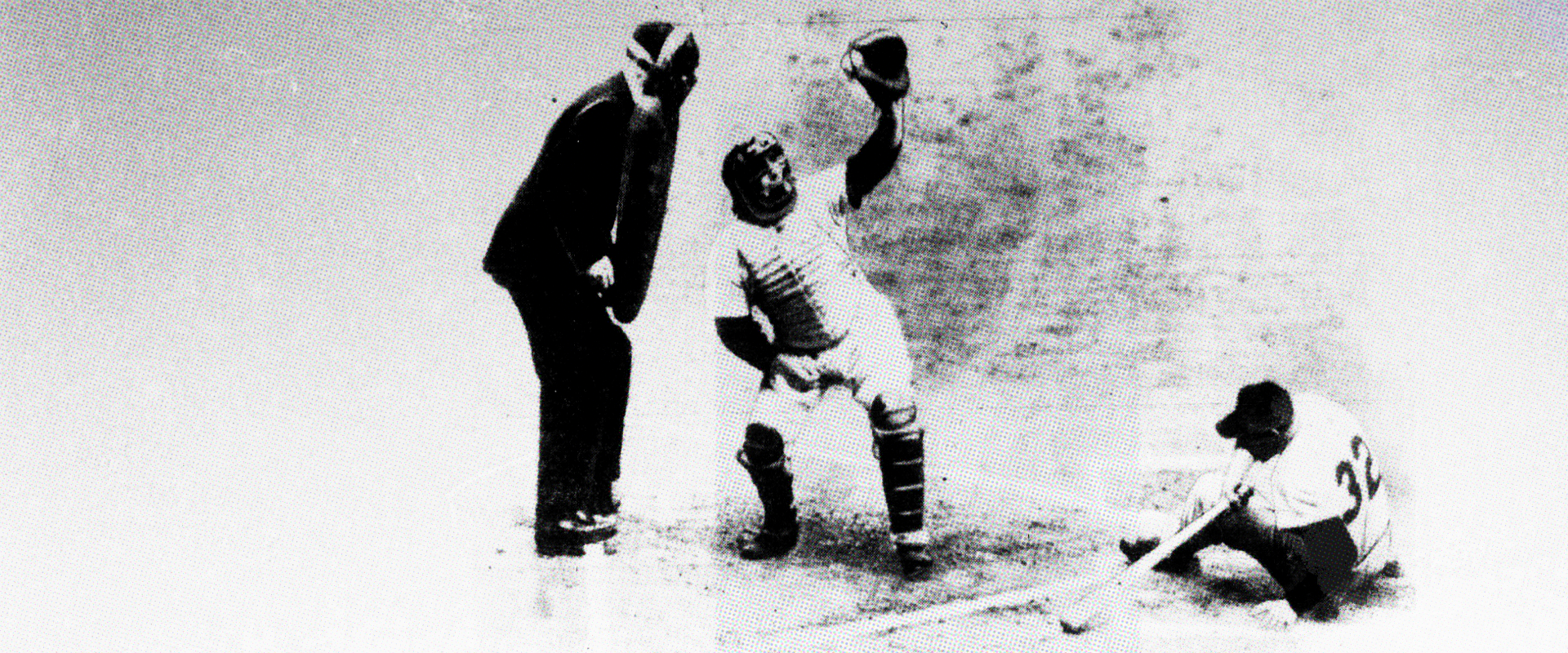

The U.S. president increased his pressure on the Federal Reserve by “firing” Governor Lisa Cook on August 26. It will likely take some time for the outcome of this action to be resolved. Since the Treasury-Fed Accord in 1951, when the Fed gained independence over its interest rate policy, at least five administrations have tried to pressure the Fed to loosen monetary policy. So far, the batting average at best is only one for five. Why do most attempts to influence the Fed end in a strikeout?

There are several safeguards against political influence affecting the Fed’s monetary policy. The primary safeguard is the Fed’s “independence.” A president cannot fire the Fed chair (or a governor) for disagreements over monetary policy. In addition, the Fed chair does not control the Federal Open Market Committee’s (FOMC) policy decisions. Rather, there are 12 members of the committee, and they strive to reach decisions by consensus. Importantly, there is also a strong culture at the FOMC of approaching its policy task in an apolitical manner, focusing only on accomplishing its dual mandate from Congress.

If a president is unhappy with the Fed, then the president can try to influence monetary policy when the chair’s term ends by appointing a replacement who is more aligned with the president’s views. How successful is this approach likely to be at influencing the Fed’s policy?

All Fed governors must be confirmed by the Senate. This is the first safeguard against a candidate with extreme views assuming the role of Fed chair. The second safeguard is that after they take office, appointments to the Fed chair do not always end up supporting the policies favored by the administration that appointed them. An example is President Harry S. Truman’s appointment of William McChesney Martin. President Truman is reported to have called Martin a “traitor” after the Fed later raised interest rates.

The president has nominated Stephen Miran to serve out the remaining term of Governor Adriana Kugler, which ends in January. A likely scenario is that in January the president will then select an individual who is his preferred “outside” candidate for the Fed chair. Shortly thereafter in May 2026, Chair Jerome Powell’s term ends. It is customary that if a Fed chair is not reappointed to a new term, the chair also resigns from the board. This would give the president another governor position to fill in 2026. The president would then appoint from the Board of Governors the next chair to a four-year term.

It would appear, then, that by mid-2026 the president would have the opportunity to make two appointments (or three depending on the resolution of the Governor Cook firing) to the board and, with any other sympathetic governors and/or presidents on the FOMC, would be building toward a majority coalition.

However, what is likely is not inevitable. If Chair Powell is concerned about his potential replacement, he can choose to “step down but not step out” of the board. He has the option to serve out his remaining term as a governor, which does not end until January 2028. Has this ever happened? There is one example of a chair making this decision. Marriner S. Eccles remained on the board until 1951 after concluding his term as board chair in 1948. How well did this unusual decision work out for Eccles? Well, the Fed put his name on its main building in Washington, D.C. — ironically, the very same building that is at the center of the current renovation fracas.

Finally, there is one more outcome that is even more remote but still possible. There are in fact two chair roles at the Fed. The first is the board chair, and the second is the FOMC chair. We typically refer to them together, since the same individual has always served in both roles. Specifically, the president appoints a governor to be the board chair for a four-year term.

However, in January of each year the FOMC elects the FOMC chair and vice chair to serve for that year. In the past, these choices have always been the board chair and the president of the New York Fed. However, according to the FOMC’s Rules of Organization: “… the Committee elects a Chair and Vice Chair from among its membership.” That is, if Powell stepped down but did not step out and a majority of the FOMC was deeply concerned about the new board chair maintaining its apolitical culture, the committee could elect Powell to continue to be the FOMC chair in 2026, and again, if necessary, in 2027.

As Yogi Berra said, “In theory there is no difference between theory and practice. In practice there is.” While it feels like we are in the bottom of the 9th, this game may go into extra innings.

Joseph Tracy is a Distinguished Fellow at Purdue University’s Daniels School of Business and a nonresident senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. Previously he was executive vice president and senior advisor to the president at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. He regularly contributes insightful posts about financial markets to Daniels Insights.