11-24-2025

Can you remember the last time that inflation was within 10 percent of the Federal Reserve’s target of 2 percent — that is, inflation was between 1.8 and 2.2 percent? You can be forgiven if you can’t remember, since memory tends to fade with time and it has been a long time. On a 12-month basis, PCE (Personal Consumption Expenditures) inflation was last close to the Fed’s target back in February 2021 — four years and eight months ago. Or, as my young grandchildren would say, “for a lifetime.”

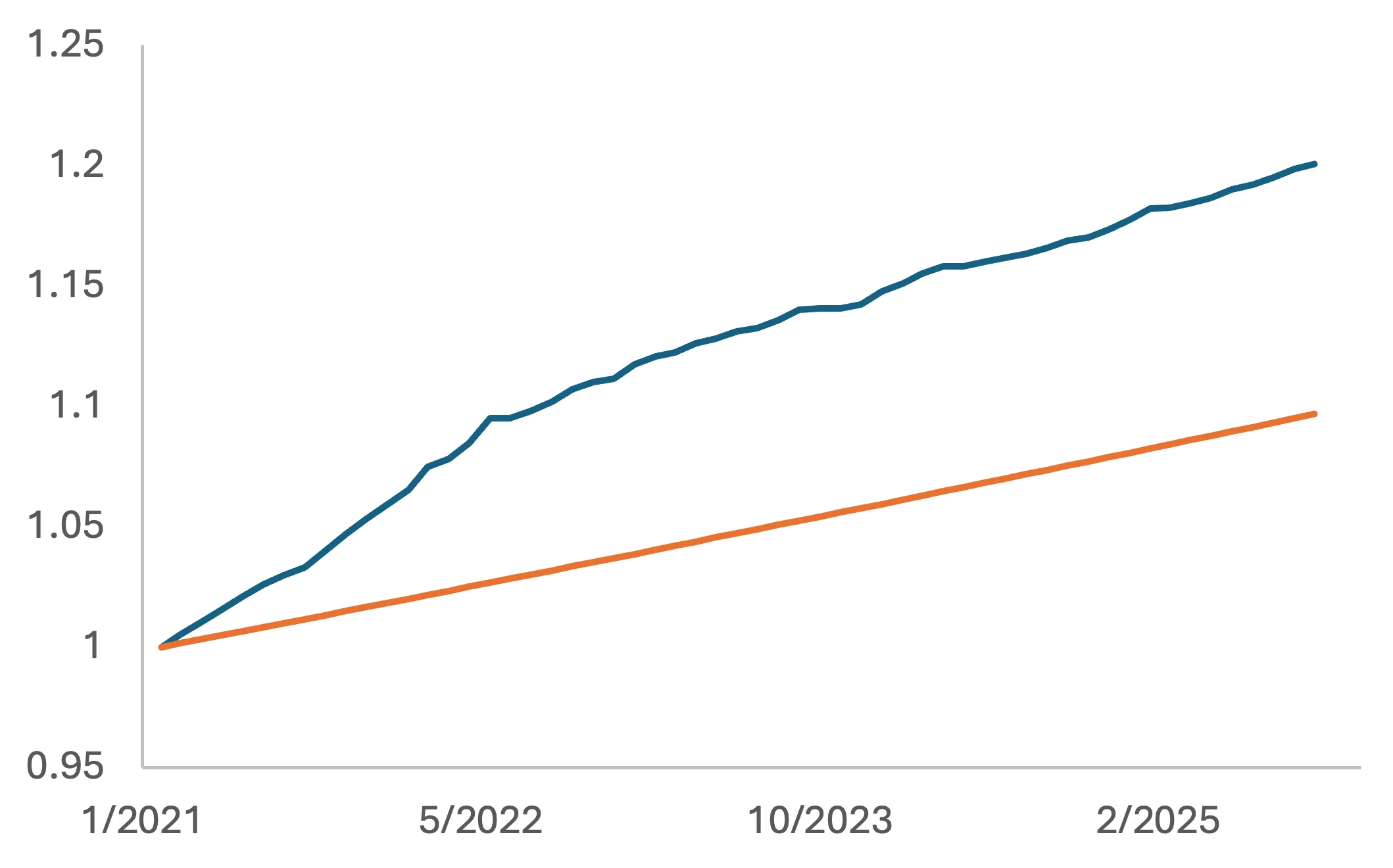

A lot of inflation has happened over this time period. The chart below shows the actual PCE price index (in blue) versus a “price stability” baseline index (in orange) where from February 2021 onwards inflation is consistently at 2 percent. Both indices are set to a value of one for February 2021.

Note: Due to the government shutdown, official PCE inflation for September and October 2025 are not available and consensus forecasts are used.

The inflation overshoot that began in early 2021 accelerated in the second half of 2021 and the first half of 2022 and has been steadily increasing to the present. As of October, the cumulative gap has grown to double digits, reaching 10.4 percentage points. When people say that things seem more expensive today, they are correct.

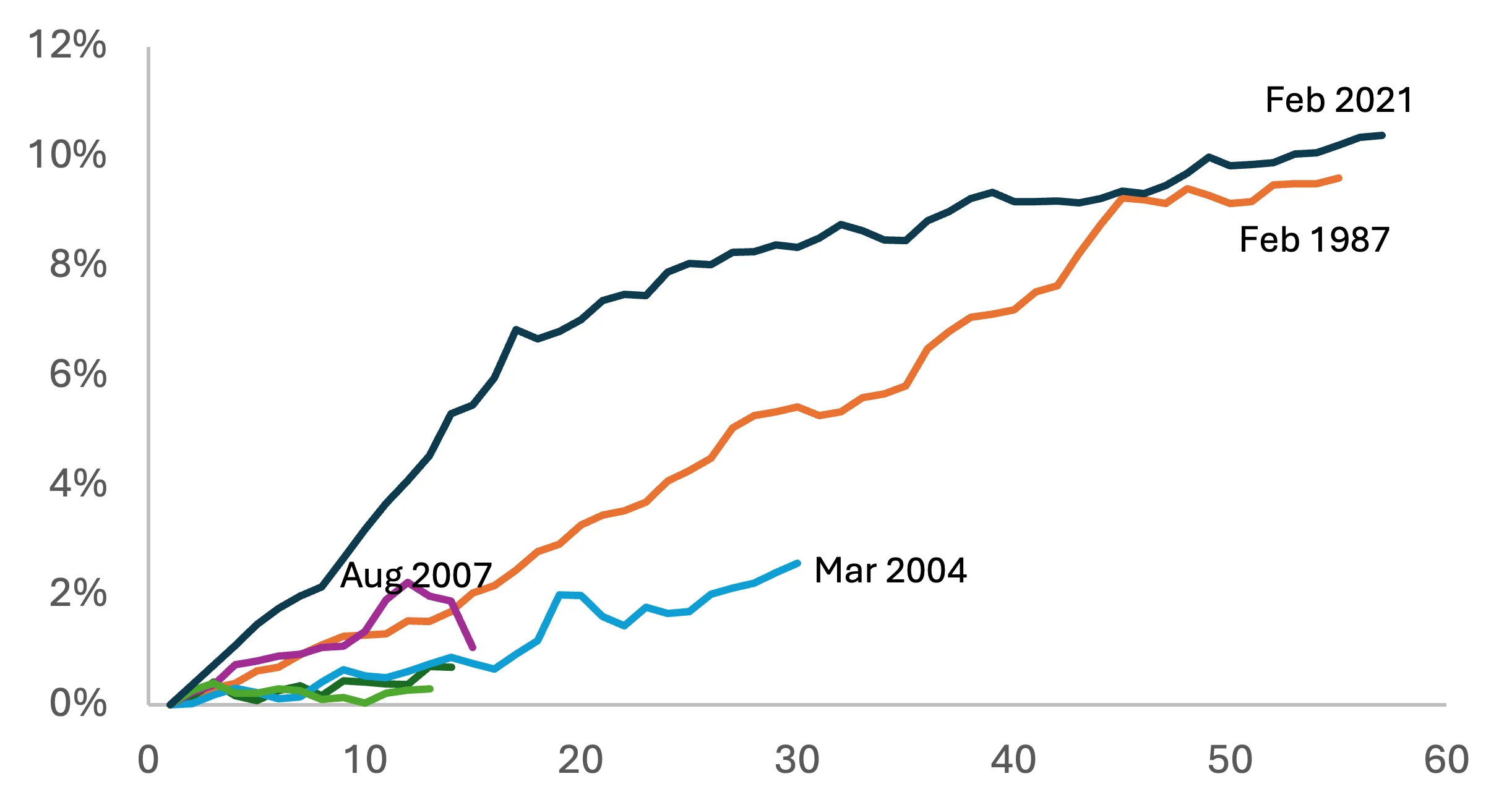

How does this inflation overshoot compare to other historical examples? I will exclude the “great inflation” of the late 1970s and early 1980s, since this was the worst inflation performance for the Fed since it gained its policy independence in 1951. I include all other cases where the Fed was close to its target and subsequently the economy experienced above-target inflation for at least a year. There are six such episodes shown in the chart below. The horizontal axis tracks the duration of each overshoot in months. The vertical axis tracks the cumulative inflation overshoot.

The two shortest episodes started in January 2000 and March 2011 (in light and dark green, in the graph above) and are not labeled. The overshoot that began in March 2004 lasted for 30 months but was modest in magnitude even for this duration, with a cumulative overshoot topping out at 2.6 percent. The closest example to what we are currently experiencing was the episode that began in February 1987 and lasted 55 months. This episode progressed slower than the current episode but accelerated toward the end, producing a maximum overshoot of 9.6 percent.

As shown in the chart, the Fed’s current inflation overshoot is the longest and largest outside of the Great Inflation. The current inflation overshoot is also expected to continue for some time. In the Fed’s September Summary of Economic Projections (SEP), the median expectation was that PCE inflation would not come back to the target until 2028. This prediction, if realized, would extend the current inflation overshoot to seven years and to an even larger cumulative magnitude.

With this poor performance record on inflation, we might expect to hear from the Fed an unwavering resolve to bring inflation back down to target in the most expeditious manner possible. What inspiring calls to action have we heard this year from key Fed leadership?

These comments do not evoke a Churchill resolve. The Fed is choosing to focus on a potential future problem in the labor market rather than the current problem with inflation. In its desire to engineer a “soft landing,” the Fed has managed to engineer no landing at all. Instead of steadfast commitment, the Fed appears to be complacent on inflation.

Presidents Hammack, Logan, and Schmid have expressed some urgency for the Fed to get inflation back on target. Let’s hope their concern is contagious with their colleagues on the FOMC. Getting inflation back down to 2 percent will be even more difficult if the public and markets react to the Fed’s complacency by increasing their inflation expectations. For the Fed to win its fight against inflation, it needs the public and markets to believe they will win. The Fed can’t take this belief for granted.

Joseph Tracy is a Distinguished Fellow at Purdue University’s Daniels School of Business and a nonresident senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. Previously he was executive vice president and senior advisor to the president at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. He regularly contributes insightful posts about financial markets to Daniels Insights.