Organizations’ pursuit of various certifications or rankings is nearly ubiquitous, with a concomitant rise in certifications for which organizations can compete. Research touts the benefits of such rankings and certifications, particularly those recognizing “best employers,” “best places to work,” and the like. Yet, there are reasons to consider a more balanced view of employee-related ranking and certification effects. For example:

We address some of these issues in a recent paper published in the Journal of Organizational Behavior. In it, my coauthors and I report two studies that mostly examined the promotion constraint and high performer turnover questions.

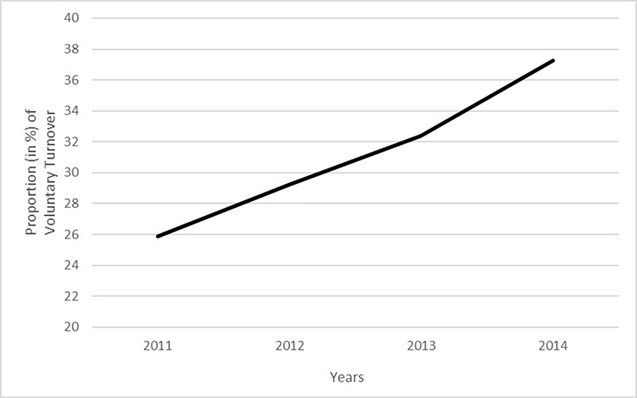

Study 1 focused on organizations that have attained what we characterize as “perennial elitism” when it comes to employee-focused recognition; i.e., being ranked in the top 10 in a particular “Best Places to Work” (BPTW) competition year after year (for our purposes, at least four years). For these organizations, we specifically examined the turnover of what were considered the “best performing employees” on an annual basis. In these elite organizations, we found that proportions of voluntary turnover comprising high performers increase over associated BPTW ranking cycles. This provides preliminary evidence suggesting that high performer turnover is adversely affected when perennial rankings are achieved (i.e., greater percentages of high performers turn over in the wake of these repeated rankings). This is illustrated below:

For example, “26” in 2011 means that, of the total voluntary turnover across elite BPTW organizations in 2011, 26% of it comprised high performers.

In Study 2, we sought to examine some potential reasons for this effect. We first conducted 40 interviews among employees in an elite BPTW organization. Two themes emerged. First, some employees interpreted BPTW success as restricting opportunities for advancement within the organization. This is consistent with research showing an overall decrease in turnover among BPTW organizations. However, in line with the possibility that certain high performers might leverage the branding benefits of BPTW recognition, some employees also perceived BPTW success as a means of building their own personal resumes.

Based on these initial findings, we conducted an empirical study of employees at this elite BPTW organization, specifically testing “perceived promotion constraint” and “perceived resume building” as two potential reasons why higher performers might turn over. We found that perceived promotion constraint helped explain the relationship between performance status and turnover intentions. That is, higher performers were more likely to perceive promotion constraints in this organization. In turn, this promotion constraint made them more prone to expressing turnover intentions.

Taken together, results across these two studies suggest that organizations should carefully consider the ramifications of branding initiatives surrounding their pro-employee and working well efforts. It would be shortsighted to suggest that organizations curtail such efforts as a way to retain top performers. Conversely, we view promotion constraint as a situation of healthy competition in organizations that results from many people desiring to work for them. Indeed, when and if higher performers do turn over, promotion constraint implies that there are others “waiting in the wings” to be promoted and fill vacancies. Moreover, the benefits of moderate turnover are well documented, in terms of innovation and diversity.

In addition, high performers who leave may do so to join a collaborating organization, increasing their prior organization's reach and building mutually beneficial bonds between the two organizations. High performers who leave elite employee-focused organizations may also act as “brand ambassadors,” speaking positively about how their former employer treated them. The literature on boomerang employees also suggests that high performers who exit an elite BPTW for career-enhancing opportunities may return when desirable positions become available. In this instance, the organization may benefit from the knowledge, skills, networks, and experience those high performing ex-employees have gained. At the same time, it seems important for organizations who achieve BPTW ranking success to consider ways to further encourage high performers to stay. For example, by identifying high performers early, providing them with regular mentoring, and enabling growth and development opportunities, organizations might increase the likelihood of retaining them.

Brian Dineen is the Frederick & Alice Leeds Professor of Management in the Organizational Behavior/Human Resources area at Purdue’s Mitchell E. Daniels School of Business.