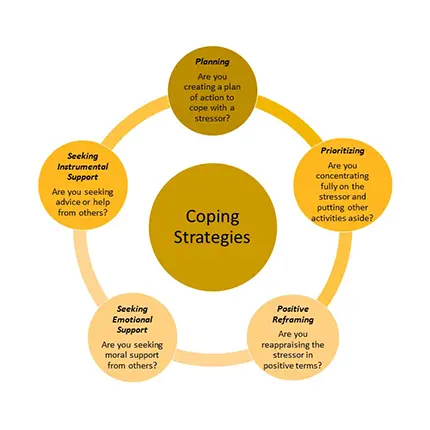

How do you cope with your work and nonwork demands? Research outlines multiple adaptive coping strategies for successfully managing stressful demands, including:

Previous research typically focuses on each coping strategy separately. However, some recent work has started to examine coping “profiles” or whether people use several coping strategies in combination to manage a specific stressor. Building upon this approach, my coauthors and I conducted three studies to examine how individuals cope with demands that impact both their work and nonwork domains (e.g., caring for a sick child or helping a friend in need during the workday) and whether employees engage in more than one strategy simultaneously.

Previous research typically focuses on each coping strategy separately. However, some recent work has started to examine coping “profiles” or whether people use several coping strategies in combination to manage a specific stressor. Building upon this approach, my coauthors and I conducted three studies to examine how individuals cope with demands that impact both their work and nonwork domains (e.g., caring for a sick child or helping a friend in need during the workday) and whether employees engage in more than one strategy simultaneously.

Study 1 was conducted with university employees at two time points during the COVID-19 pandemic. Time 1 occurred during lockdown (April 2020) and three coping profiles emerged. These profiles included: individualistic copers (employees who engaged in high levels of planning, prioritizing and positive reframing, and lower levels of seeking support from others), emotion-focused copers (higher use of seeking emotional support and positive reframing, and lower use of planning, prioritizing and seeking instrumental support), and comprehensive copers (employees who engaged in high levels of all five coping strategies). At Time 2 (when lockdown restrictions were being lifted and our sample returned to at least some in-person work in September 2020), four profiles emerged including the same three from Time 1, plus surviving copers (characterized by moderate levels of all five coping strategies).

Overall, in Study 1 we found that employees who were individualistic copers throughout the study experienced lower work and well-being outcomes—they had lower task adaptability, thriving, and life satisfaction, and increased feelings of stress. Similarly, those who transitioned into surviving copers also experienced decreased task adaptivity and life satisfaction, as well as increased stress. Finally, we found that those who were comprehensive copers during the entire study experienced increased stress. This suggests that coping at full capacity over time taxes our personal resources, and the best approach may be to more efficiently cope by engaging in one form of support seeking (e.g., emotional or instrumental) and one other strategy (e.g., planning).

Study 2 was conducted in late 2022 with a sample of full-time working adults from various industries with the goal of seeing whether our coping profiles replicated. Supporting our findings from Study 1, Study 2 replicated the majority of our coping profiles from the pandemic, except emotion-focused copers, and also uncovered one new profile. The new profile, constrained copers, includes employees who engage in low levels of all five coping strategies, suggesting that another study was needed to continue to examine the profiles of copers that may emerge and the implications of coping profiles for employee performance and well-being.

Study 3, which was conducted in early 2023 with a sample of full-time working adults at two time points, demonstrated the same four profiles as Study 2. Similar to the Study 1, results suggested that employees who transitioned into surviving copers experienced decreased task adaptability and thriving at work, as well as decreased recovery at home. This suggests that employees who attempt all five coping strategies to some extent (but not fully) experience reduced work and well-being outcomes. Employees who remained comprehensive copers experienced the benefit of increased task adaptivity, but also increased conflict with coworkers.

Taken together, results across our studies suggest that it is crucial to find the right mix and depth in coping strategies—something that training programs or resource groups in organizations could help facilitate. It also means that clear and supportive management practices for approaching work and family demands are needed (e.g., managers can help employees plan and prioritize their work tasks and give employees flexibility for handling family needs).

Our research suggests that employees need multiple adaptive coping strategies to successfully manage work and nonwork demands. These strategies include planning, prioritizing, positive reframing, seeking emotional support, and seeking instrumental support. Previous research typically focuses on each coping strategy separately; our research suggests that focusing more on combinations of coping is advantageous. Our research suggests that the best approach to efficiently coping may be to engage in one form of support seeking and one other strategy.

Kelly Schwind Wilson is a Professor of Management in the organizational behavior and human resources area at Purdue's Mitchell E. Daniels, Jr. School of Business