08-06-2025

When the Fed was established in 1913, Congress did not give it an inflation mandate. Rather, Congress directed the Fed to “furnish an elastic currency, to afford means of rediscounting commercial paper” and “to establish a more effective supervision of banking in the United States.” This was in response to the Panic of 1907 and the associated bank failures. At the time, the gold standard was assumed to be all that was necessary to keep inflation low and stable.

In the long shadow of the Great Depression, Congress passed the Employment Act of 1946, which stated that federal government policy was “to promote maximum employment, production and purchasing power.” This shared responsibility extended to the Fed.

Over 50 years later, in a period of high inflation and unemployment, the Federal Reserve Reform Act of 1997 gave the Fed the mandate of “promoting effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices and moderate long-term interest rates.” A year later, the Humphrey-Hawkins Full Employment Act narrowed this list to “maximum employment and stable prices” — creating the Fed’s dual mandate.

This is in contrast to other major central banks that have a sole focus on price stability. The European Central Bank’s mandate is “maintaining price stability, defined as keeping inflation low, stable and predictable.” The Bank of England’s mandate is to “maintain price stability and, subject to that, support the government’s economic policy.” Finally, the Bank of Japan’s mandate is to “achieve price stability and ensure the stability of the financial system.” An advantage of a single mandate is that it creates a clear division of responsibility on economic policy. The Central Bank is accountable for inflation through monetary policy. The administration is accountable for economic growth through fiscal policy.

How can the Fed accomplish two goals with essentially one policy tool? This depends on the situation the Fed is facing. If inflation pressure is being generated by “excess demand,” then the Fed can support both sides of its mandate through tighter monetary policy. However, if inflation pressure is being generated by “supply shocks,” then the Fed must make a choice of which side of its dual mandate to support. That is, the Fed’s dual mandate becomes a “duel” mandate. The Fed must decide which of its two mandates to focus on. If the Fed fights inflation, economic growth will slow further. If the Fed supports economic growth, then inflation will worsen.

What situation does the Fed confront today? In an update to Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium (DSGE) model, there are two takeaways. The first is that “the model points to a marked weakening in real GDP growth across the forecast horizon.” The second is that “core PCE inflation forecast has been revised significantly higher in the near term, with moderate upward adjustments in later years, reflecting persistent cost pressures.” This outlook was described by the New York Fed President John Williams in remarks at the New York Association for Business Economics on July 16, 2025. President Williams said, “I expect real GDP growth this year to be about 1 percent,” and “I anticipate inflation will come in between 3 and 3 1/2 percent in 2025.” This is directionally consistent with the relatively weak labor market report and the increase in the 12-month Dallas Fed’s Trimmed Mean PCE inflation from 2.6 to 2.7 percent.

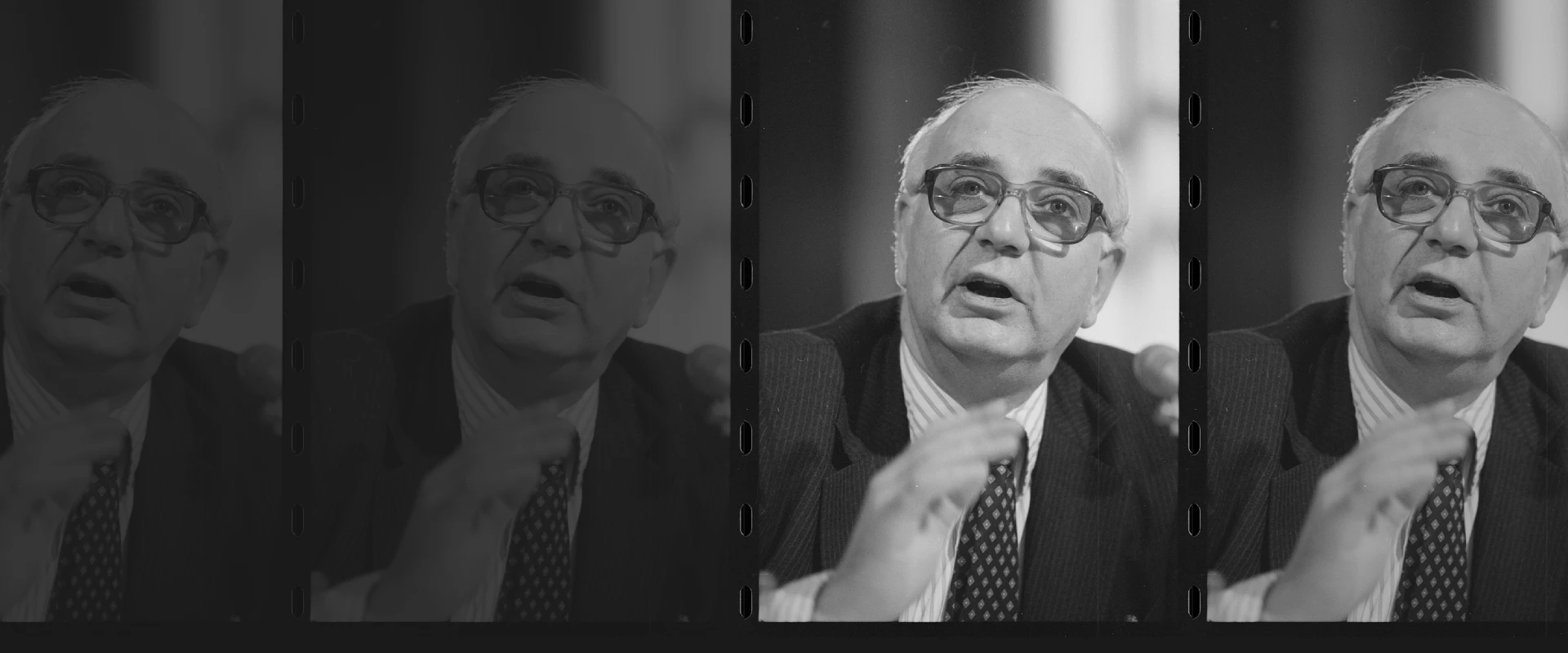

This is not the first time that the Fed has needed to pick which side of its mandate to support. Chair Paul Volcker faced this situation as he battled to reduce the high inflation of the late 1970s. He justified the Federal Open Market Committee’s focus on the inflation side of the dual mandate in his February 25, 1981, testimony to the Senate Banking Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs.

Senator Harrison Williams (NJ): “I see very little in your submission — and I haven’t been here through the entire morning of your testimony, but I’m told there is very little in your testimony about full employment. I just wonder what will the Fed monetary Policy do for employment, and also why is there so little mention of full employment in the current debate over fiscal and monetary policy?”

Chair Volcker: “I am wholly convinced — and I think I can speak for the whole board and whole Open Market Committee — that recognizing that the objective for unemployment cannot be reached in the short run. The kinds of policies we are following offer the best prospect of returning the economy in time to a course where we can combine as full employment as we can get with price stability. I bring in price stability because we will not be successful, in my opinion, in pursuing a full employment policy unless we take care of the inflation side of the equation while we are doing it.”

In these situations, the independence of the Federal Reserve is crucial. The Fed must be allowed to focus on the inflation side of its mandate. Whether duels are fought in Weehawken or Washington, D.C., prevention beats cure. The best alternative is to address the underlying policies generating the tensions between inflation and growth. Having administrations pursue consistent policies to support long-run economic growth is the best way to keep the duel out of the Fed’s dual mandate.

Joseph Tracy is a Distinguished Fellow at Purdue University’s Daniels School of Business and a nonresident senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. Previously he was executive vice president and senior advisor to the president at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. He regularly contributes insightful posts about financial markets to Daniels Insights.