01-30-2025

In August 2020, the Federal Reserve announced revisions to their operating framework for monetary policy. One change they adopted was a Flexible Average Inflation Targeting (FAIT) approach, which I discussed in earlier Daniels Insights blog posts. A second change was to adjust their policy rate in response to “shortfalls” rather than “deviations” in the unemployment gap — that is, only when there is slack in the labor market.

Recall that the Taylor Rule provides a benchmark for calibrating monetary policy. The Taylor Rule has three components: the neutral Federal Funds rate, the inflation gap and the unemployment gap. The last two reflect the Fed’s dual mandate from Congress of stable prices and maximum sustainable employment.

The Taylor Rule assumes that the Fed will react in a symmetric manner in adjusting its policy rate to positive and negative inflation and unemployment gaps. The Fed tightens monetary policy in response to positive inflation and unemployment gaps and loosens monetary policy in response to negative inflation and unemployment gaps. The change in the framework leaves the Fed’s response to the inflation gap unchanged. However, the new framework indicates that the Fed will no longer tighten monetary policy in response to positive unemployment gaps (i.e. “tight” labor markets).

The rationale given is that tight labor markets benefit workers by creating more employment options and higher wages. The concern that higher wages would lead to inflation were allayed by the view that anchored inflation expectations had “flattened” the Phillips curve relationship between unemployment and inflation.

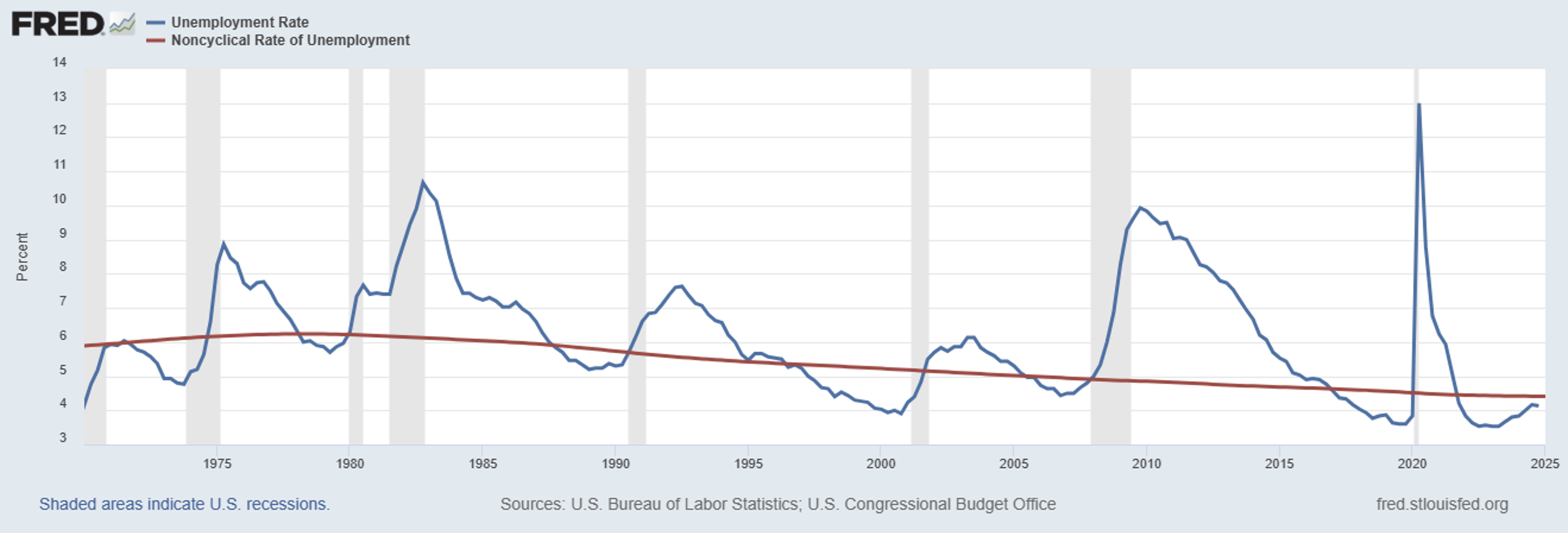

How convincing is this argument? The figure below shows the unemployment rate and an estimate of the natural rate of unemployment from 1970 to present. While the unemployment rate is quite cyclical, the natural rate of unemployment changes slowly over time reflec evolving characteristics of the workforce. Negative (positive) unemployment gaps exist when the unemployment rate (blue line) exceeds (is below) the natural rate (red line). An exceptionally large positive (and short lasting) unemployment gap was created during the COVID-19 health crisis.

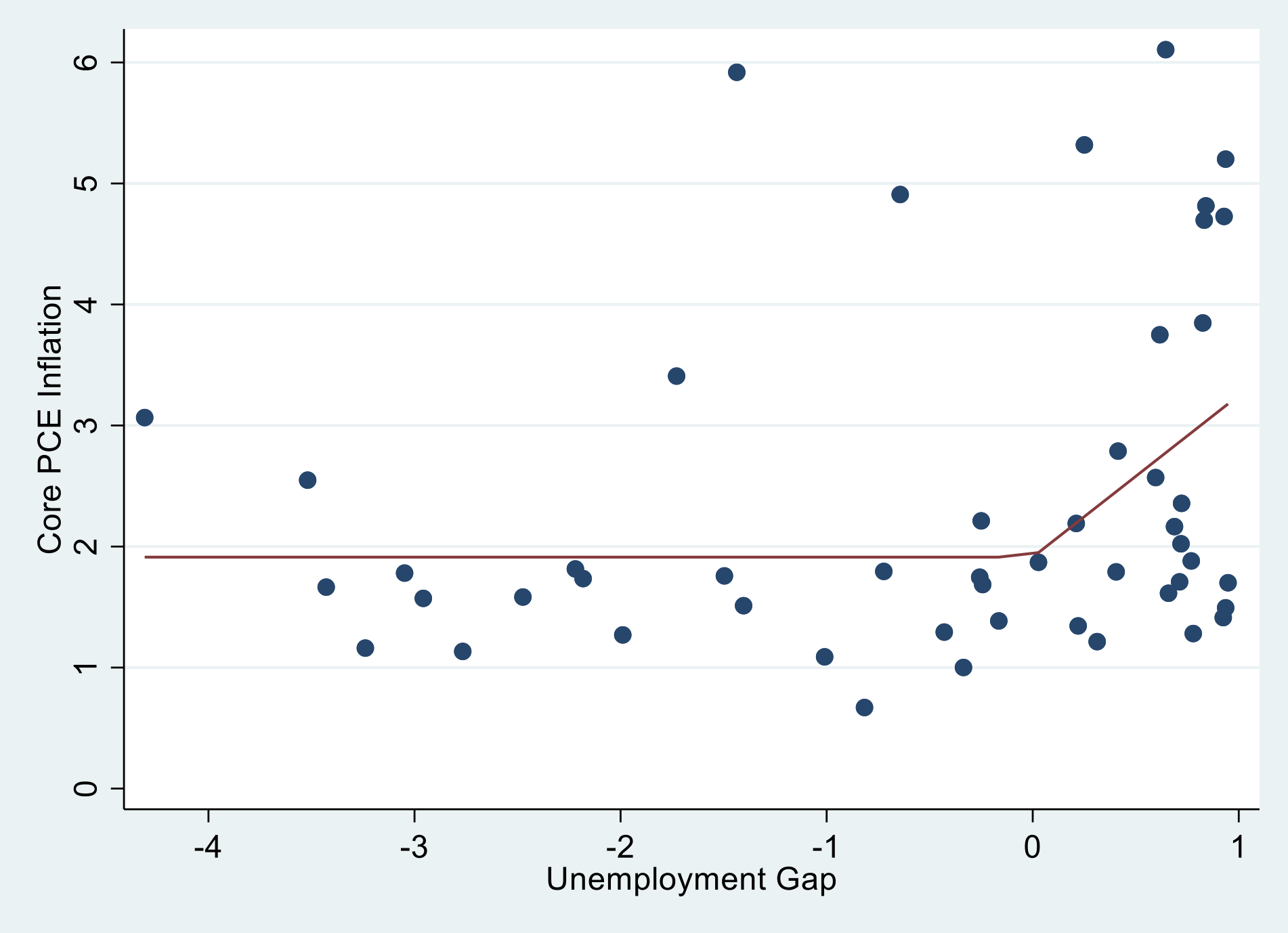

To check out the flattening hypothesis, we can look at the relationship between quarterly unemployment gaps and Core PCE inflation. We can restrict our attention to the period from 2012 onwards after the Fed announced its 2 percent PCE inflation target that was intended to help anchor inflation expectations. We exclude the large positive unemployment gap created by COVID-19 since it is an outlier. The data for this period is shown in the figure below.

If we statistically fit the best line to the data allowing the line to change its slope at a zero unemployment gap, the data indicate no relationship between negative unemployment gaps and Core PCE inflation with the predicted inflation at 1.9 percent. However, the data indicate that tight labor markets are associated with higher inflation. This line does not line up with the flattening hypothesis.

The Fed’s changes to its operating framework included moving from treating positive and negative unemployment gaps (deviations) in a symmetric fashion as reflected in a Taylor rule, to only responding to negative unemployment gaps (shortfalls). Even though the data since 2012 does not indicate that slack labor markets lead to lower inflation, easing monetary policy in response to negative unemployment gaps stimulates hiring and reduces unemployment. This supports the second half of the Fed’s dual mandate.

On the face of it, not raising its policy rate in tight labor markets would seem to embrace faster nominal wage growth. However, this may not lead to faster real wage growth if inflation is also higher. As always, be careful what you wish for.

Joseph Tracy is a Distinguished Fellow at Purdue University’s Daniels School of Business and a nonresident senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. Previously he was executive vice president and senior advisor to the president at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.