09-06-2024

The unemployment gap is the difference between the natural rate of unemployment and the actual unemployment rate. When the unemployment gap is negative, there is “slack” in the labor market and the Fed should reduce its policy rate to stimulate hiring. Similarly, when the unemployment gap is positive the labor market is “tight” and, in the past, the Fed has increased its policy rate to prevent “overheating.”

In 2019, the Fed announced a new policy framework. One component was that the Fed would no longer tighten monetary policy in response to a positive unemployment gap. The reasoning was that tight labor markets lead to higher wage gains benefiting, in particular, lower-skilled workers. A risk in this new approach is that if ignoring a tight labor market raises the risk of a future recession, the same workers the Fed was trying to help will pay a disproportionate share of the resulting costs of unemployment. Leaning against a tight labor market may produce more sustainable wage gains.

Neither the inflation gap nor the unemployment gap is directly observable and, instead, both must be estimated. Earlier, I discussed measures of underlying inflation that can be used to estimate the inflation gap. To measure the unemployment gap, we need an estimate of the natural rate of unemployment—that is, the unemployment rate that would exist if the economy were growing at its potential.

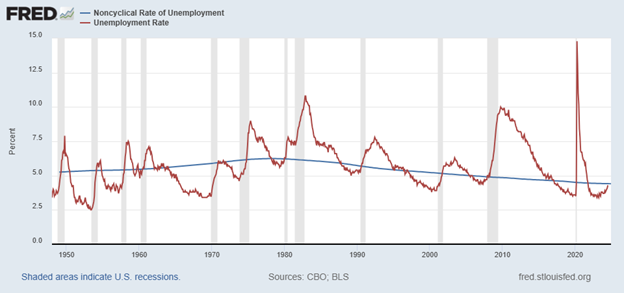

The most commonly used measure of the natural rate of unemployment is produced by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). Movements in the CBO’s natural rate of unemployment reflect changes over time in the makeup of the labor force. As the labor force becomes more educated and older, the natural rate of unemployment declines. This can be seen in the figure below where the estimated natural rate of unemployment has been slowly declining since the early 1980s.

The onset of Covid-19 and the policy responses led to a sharp upward spike in the unemployment rate in 2020. However, the slack in the labor market was eliminated by the end of 2021. The labor market continued to tighten in 2022, creating a positive unemployment gap. In March 2022, when the Fed started raising its policy rate, the unemployment gap was 0.84, indicating a tight labor market. By July 2024, a year after the Fed stopped raising its policy rate, the unemployment rate had drifted up to 4.3 percent essentially closing the unemployment gap. This indicates that current monetary policy can be calibrated using just the inflation gap and the Taylor Principle.

Joseph Tracy is a Distinguished Fellow at Purdue University’s Daniels School of Business and a nonresident senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. Previously he was executive vice president and senior advisor to the president at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.