12-19-2024

The Federal Reserve’s decision not to tighten monetary policy until March 2022 has been the subject of debate. In my last post, “What’s Past is Prologue,” I argued that understanding the problem that the Fed had been facing for almost a decade prior to the COVID-19 health crisis is helpful for insight into how it reacted to events in 2021.

Let’s review. From January 2012, when the Fed defined its mandate of price stability as PCE inflation at 2 percent, up until August 2020 when it changed its monetary policy framework to say its goal was to have PCE inflation average 2 percent over time, the Fed consistently missed its inflation target. However, the problem was that PCE inflation was consistently below 2 percent. The new Flexible Average Inflation Targeting (FAIT) approach was intended to reassure market participants that the Fed would rectify this problem in order to keep long-run inflation expectations anchored at 2 percent.

As shown in Figure 1, the Dallas Trimmed Mean inflation hit 2 percent in May of 2021 — a little more than a year following the $1.9T American Rescue Plan. A month later, Chair Powell described the upward pressure on inflation as the result of temporary supply bottlenecks and repeated this assessment in August in his Jackson Hole address.

The Fed waited until March 2022 to begin to tighten monetary policy. At this point, Trimmed Mean PCE inflation was almost 4 percent — double the Fed’s target. To many, this long delay seemed inexplicable, even if one believed that supply chain problems played a role in the higher inflation.

However, let’s look at the situation in mid-2021 from the perspective of the problem that the Fed had faced over the prior 10 years. The Fed announced in August 2020 its new policy framework that proclaimed to markets that after a period of undershooting its inflation target the Fed would not immediately react to inflation rising above 2 percent. This was to convince markets that, despite its track record up to then, going forward the Fed would achieve inflation averaging 2 percent over time. If we take the Fed at its word on its new framework, like Horton from Dr. Seuss who exclaimed “I meant what I said, and I said what I meant,” then we get a different perspective on the Fed’s timing of its initial rate increase.

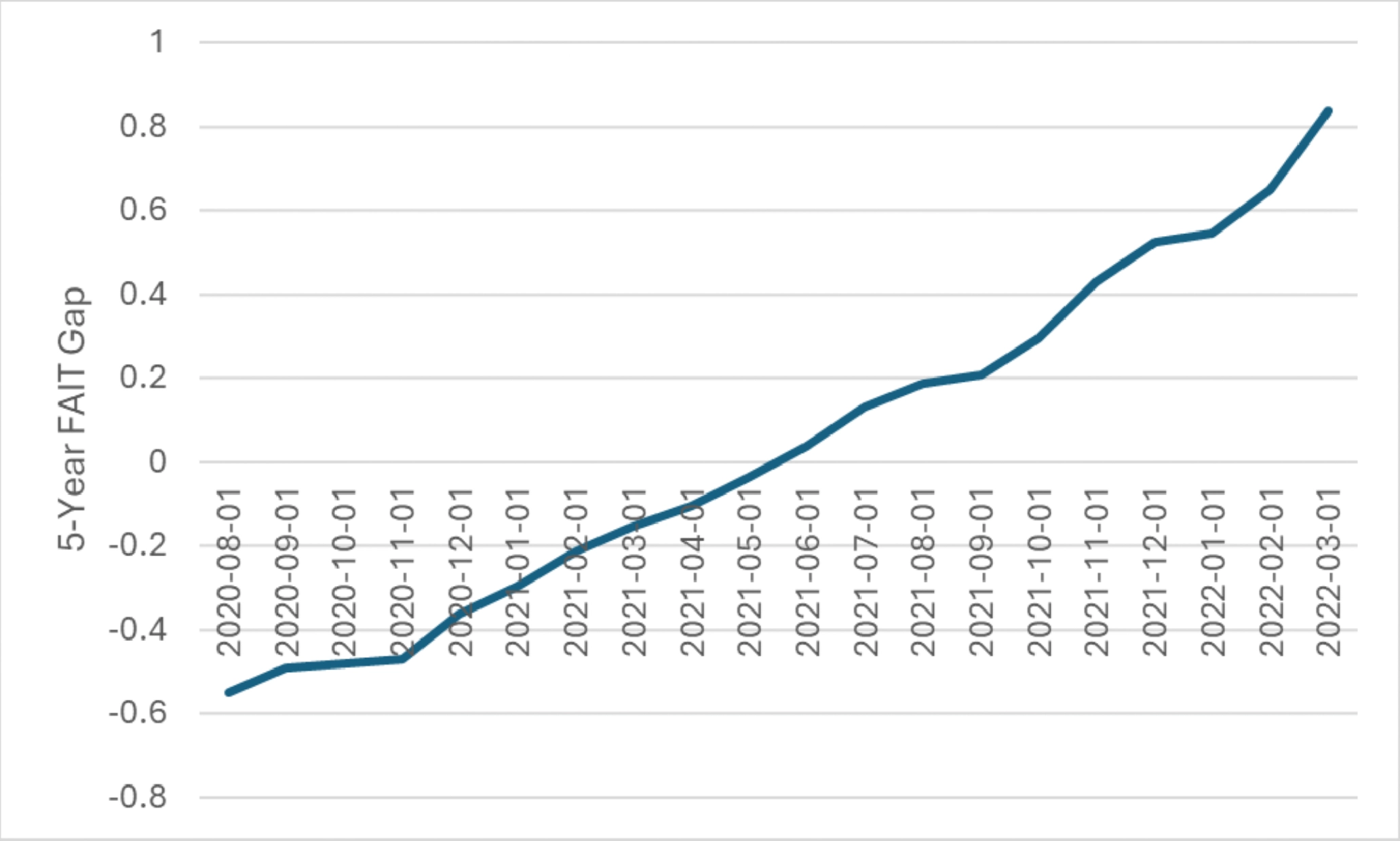

While the Fed’s new policy framework did not specify a time window that it expected to average 2 percent inflation, let’s assume that they had a 5-year window in mind. What did things look like from the vantage point of a 5-year FAIT perspective? A simple metric is the deviation of the 5-year compound average PCE inflation rate from the Fed’s 2 percent target. Figure 2 shows this metric starting from the announcement date of the new framework.

When the Fed announced its new monetary policy framework in August 2020, the 5-year compound average PCE inflation rate fell short of the Fed’s 2 percent target by 55 basis points. When Powell is testifying to Congress in June of 2021, the negative gap had just closed. While Powell emphasized the supply chain disruptions in the Summer of 2021, from a FAIT perspective the Fed had just paid off its inflation deficit. Up to that point, the increase in inflation could have been viewed as welcomed in that it closed the negative FAIT gap.

From the perspective of the Fed’s new FAIT framework, the initial rise in inflation above 2 percent in February 2021 provided an opportunity to show markets that they would not immediately act to reduce policy accommodation. This would help to convince markets that they “meant what they said, and said what they meant” in August 2020. The goal was to keep inflation expectations anchored at 2 percent.

Joseph Tracy is a Distinguished Fellow at Purdue University’s Daniels School of Business and a nonresident senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. Previously he was executive vice president and senior advisor to the president at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.